Chapter 9

Diary research: Understanding UX in context

Diary research is a research method which provides a deep level of intimate insight into your target user and focus area. Read on to learn how to plan, prepare, and conduct diary studies.

What is diary research?

Diary research—also known as a diary study—is a longitudinal (running over a period of time) UX research method used to collect qualitative data, through participants keeping a diary to record their thoughts, feelings, and behavior, while they use a product.

A diary study entails participants self-reporting data over an extended period of time—ranging from days to a month or longer. During this time, they’ll log specific information about activities regarding the product being studied.

Diary studies allow us to better understand the complexity of the user experience, which changes so drastically based on the use cases experienced by users, and the evolution of the product in their hands.

Matthieu Dixte, Product Researcher @ Maze

The purpose of diary studies

The main value of diary studies are their unique ability to give contextual insights about real-time user behavior and needs. Unlike other research methods—such as usability tests or user interviews, which provide observational data gathered in a lab-based situation, removed from a product’s everyday application—diary studies offer a window into the reality of users interacting with products.

Product teams can then use these organic insights to define UX features and requirements, creating a truly user-centered experience, without the guesswork.

Methods for conducting diary research

There are several methods of diary study, ranging from open diary studies which give participants freedom to use the diary as they wish, and closed diary studies which follow a tighter set of protocols. Depending on your research objectives, you’ll want to choose between the two:

- Freeform/open diary study: Similar to a personal journal, this type of study gives participants a lot of freedom in how and when they record their thoughts. You’ll still want to give subjects some initial guidance, but the diary is more free-form. This style enables less-experienced participants to take part, and people are likely to provide information you may not think to ask for, making it ideal for generative research. However, the downside is participants may not include the details you need, or include too little—or too much—information.

- Structured/closed diary study: A closed diary study uses pre-set focuses and closed-ended questions to uncover information. Structured diaries may include a page per study day, concluding questions, and explicit instructions. They are typically easier to analyze as the data will be pre-formatted across all participants. They also ensure you receive the information that’s most relevant to your study, so it’s perfect for evaluative research. The downside of this study type is that you may miss out on additional insights that don’t fit into the structure provided.

Most researchers find that the ideal method sits somewhere between freeform and structured, providing participants with a decent amount of guidance and reminders throughout the study, without overcrowding them.

The different types of diary studies

Along with deciding between an open or closed diary study, you also need to determine the type of diary you’ll be using.

There are an increasing number of ways to record diary entries, all of which broadly fall under the bracket of digital or paper. Unlike other research methods, the research tool you use for a diary study does not significantly impact the results, so the decision mostly comes down to the resources you have available (whether you can pay for an online tool or physical diaries) or personal preferences.

Paper diaries are a good, simple format for respondents, but there are big advantages to digital diary studies. You can ask follow-up questions, and have the ability to make sure respondents answer in the way you want them to. It’s also a big plus to be able to collect results little-by-little, and progress at the same pace as the analysis of results (even if sometimes it’s too early to draw conclusions.

Matthieu Dixte, Product Researcher @ Maze

Digital/online

- Digital tool e.g. dscout

- Online platform e.g. GoogleDocs

- Mobile app e.g. Indeemo

- Digital communication platform e.g. Whatsapp

Paper/offline

- A physical diary (provided by researcher or participant)

- Question sheet

- Video/audio log

Tip: The only main differentiator, other than cost, is that some digital research tools may analyze the results for you.

The benefits of diary research

There’s many reasons to opt for diary studies as your choice of research method, from a focus on micro-moments to providing real-life context to data. Let’s cover the perks of diary research.

Provides data with real-world context

One of the stand-out points of diary studies are how they convey a product’s impact within real-world context.

Diary research requires study participants to actually interact with a product in their everyday life, and record data in-situ (or shortly after). Where the majority of research methods ask participants questions outside a real-life scenario, diary studies do the opposite.

As a result, you’ll receive far more reliable, honest, and contextualized data. For example, say you’re making a travel maps app, during a usability test, users may find few issues with the app. However, in the real world, users may discover that the app doesn’t work offline and makes navigation difficult. They may realize that some of the features they use most when actually navigating, are ones they barely considered when sat in a research room.

Gaining this data is incredibly valuable, and provides key feedback points and priority for product teams, where previously they may have missed it.

Allows for a deep level of insight and micro-moments

Where some research methods reveal broad strokes of insight, diary studies scope in on the detail that builds the bigger picture.

If you want to focus on the micro-moments of user experience, diary research offers designers an incredibly detailed understanding of the users and product in question.

The purpose of a diary study is to understand long-term behaviors such as habits, changes in behavior or perception (especially if your product is evolving), motivations, customer journeys, etc.

Matthieu Dixte, Product Researcher @ Maze

One example is if you’re researching what makes users purchase a new product—asking them the question outright will likely provide a different answer than observing their thoughts and frustrations over the course of a week or longer. A longitudinal study like this will surface those micro-moments that build up, pushing someone towards a major choice.

By giving participants the opportunity to record thoughts, feelings and behaviors in the moment they happen, you also gain a deeper understanding of how your product works and impacts the user. This sort of nuance typically fades from our mind over time—where other UX research methods are a snapshot of user experience, diary research is like an HD video.

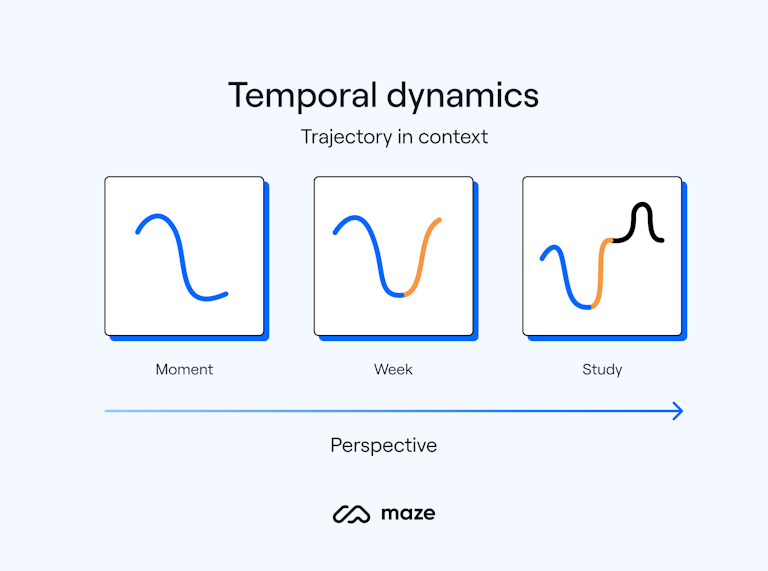

Captures how behaviors change over time

Temporal dynamics refers to how perceptions and behaviors change over time, and how they interact with and impact each other. For the sake of a product’s longevity, diary studies’ ability to reveal temporal dynamics is incredibly useful.

Diary research is one of the few research methodologies that provides respondents with autonomy, as well as a way to track their progress over time. This inherently means data is less likely to be biased in terms of the evolution of the results.

Matthieu Dixte, Product Researcher @ Maze

For a majority of UX research methods, users respond in the moment. Decisions are made on the spot, and thoughts are recorded during the test or afterwards. The perks of this is that you get gut reactions without users overthinking. However, it means your insight only goes so many levels deep.

Diary research, on the other hand, gives participants the opportunity to check in multiple times, record how their thoughts and feelings change over time, and reflect on their answers. It encourages self-discovery, providing you with a different lens of insight to consider.

Diary research’s longitudinal approach means you can understand how different events, emotions, and moments impact decisions and interactions with a product at the start of their relationship right through to consistent usage.

This view can unlock unique insights such as:

User habits and usage scenarios:

- What does a typical day look like for users; when do they engage with the product?

- What behaviors are spontaneous vs. pre-planned?

- What behaviors are sporadic, or habitual?

- When, why, and how does life interrupt usage of the product?

- What do users do before/after using the product?

- What are their workflows for completing these tasks?

Changes in behavior and perception:

- How learnable is a product?

- Do users share the product or results of using the product with others?

- Does using the product become part of their routine?

- What are users’ primary motivations for using the product—does this change?

- What are their main tasks with the product—does this change?

Attitudes and motivations:

- How do users feel before and after engaging with the product?

- How do they feel when they complete a task?

- Why do they make certain decisions?

- How do feelings and perceptions about the product change over time?

- What points of delight or friction are there?

Gathering answers to these questions enables you to develop a richer understanding of your users, and product, while also providing questions, scenarios, and research goals for future tests.

Minimize bias and the impact of observation

Even in the most carefully planned, unbiased research studies, participants are somewhat influenced by the presence of observation. Regardless of whether a study is moderated or not, participants know they are being observed—as a result, data will always be somewhat biased, however much we mitigate that.

Consider a field study; even though participants are in their natural habitat and you’re able to observe their day-to-day life, the participant will still act differently to how they do when truly alone.

Diary studies allow researchers to simulate a more personal relationship between user and study than other research methods. If the purpose of research is to truly uncover how participants interact with a product, then diary research captures this at its most natural.

The other plus side of a lack-of-observer is that—if prepared in advance—diary studies can self-run, removing some of the resources needed. Of course they still need to be monitored intermittently, but depending on how much you plan to communicate with participants, they can be fairly self-sufficient.

When should you conduct diary research?

There’s many circumstances where you may want to use diary research. Depending on your focus, the time you’ll want to conduct your study may vary.

Diary study objectives

The focus of a diary study can range from extremely specific (e.g. understanding all interactions with a specific section of a web page) to very broad (e.g. gathering general information about when people use a smartphone).

The Nielsen Norman Group suggests there are broadly four categories of diary study topics:

1. Product or website: Understanding all interactions with a product or site (e.g. a retail site) over the course of a month

2. Behavior: Gathering general information about user behavior (e.g. smartphone usage)

3. General activity: Understanding how people complete general activities (e.g. sharing information via social tools or shopping online)

4. A specific activity: Understanding how people complete specific activities (e.g. buying a new car)

The best time to conduct diary research

Diary studies can be conducted at any stage in the design process, but are typically most useful at the beginning, middle, and end:

When you’re in the discovery phase, diary research can reveal how users currently solve the problem in question, giving you valuable context to plan your own solution. Discovery-phase diary research can also be conducted on existing products or competitors, to set benchmarks or better understand the way users interact with similar products.

Testing early-stage prototypes can be done with diary research to gather information on the current success of your design, and identify any issues to address in future iterations.

At the end of development, a diary study can delve into user experience in the closest simulation to real life. This is a chance to see whether users are interacting with your product as expected, and uncover any missed opportunities for improvement.

After launch, diary research is helpful as a form of post-study interview to assess the success of a product and analyze performance in the real world; is it meeting expectations, what changes should be implemented in updates?

Diary research doesn’t necessarily take more time than other quantitative research methods. While there’s passive time of the study to take into account, it’s the analysis that is time-consuming. You’re analyzing evolutions of behavior and in-depth patterns, each focused on a different respondent’s perspective. The insight is well worth the time, but it helps to do this analysis in bits and pieces as you progress through the study.

Matthieu Dixte, Product Researcher @ Maze

Things to consider before conducting your diary study

Like most research methods, planning a diary study involves a lot of preparation. The added element of diary research being fairly hands-off, and taking place over a significant course of time, means it’s even more important to ensure you’ve not missed anything.

To help, here’s some things to consider before your study gets underway:

What type of diary are you using?

Determine what type of study you want to conduct, and the kind of diary your participants will be using.

- Open or closed: As we saw earlier in the chapter, open diaries are ideal for generative research, and closed for evaluative research. Take a look at the section above for a full rundown on the pros and cons of each, and remember to consider your research goals while deciding.

- Online or offline: Decide on the type of diary you want filled in. Consider your users—are they tech-savvy and would gel with electronic diaries? What activities are they logging—if you’re researching the durability of camping equipment, an offline diary users can travel with may work best. However, if you’re studying cosmetic preferences, then maybe a video log where participants can record their usage would make sense.

What equipment do you need?

If you’re asking participants to use a certain product, have they received a physical item, product, or prototype? Do they need instructions for it? If you’re testing a website or app, do participants have access to the platform and a copy of instructions for logging in?

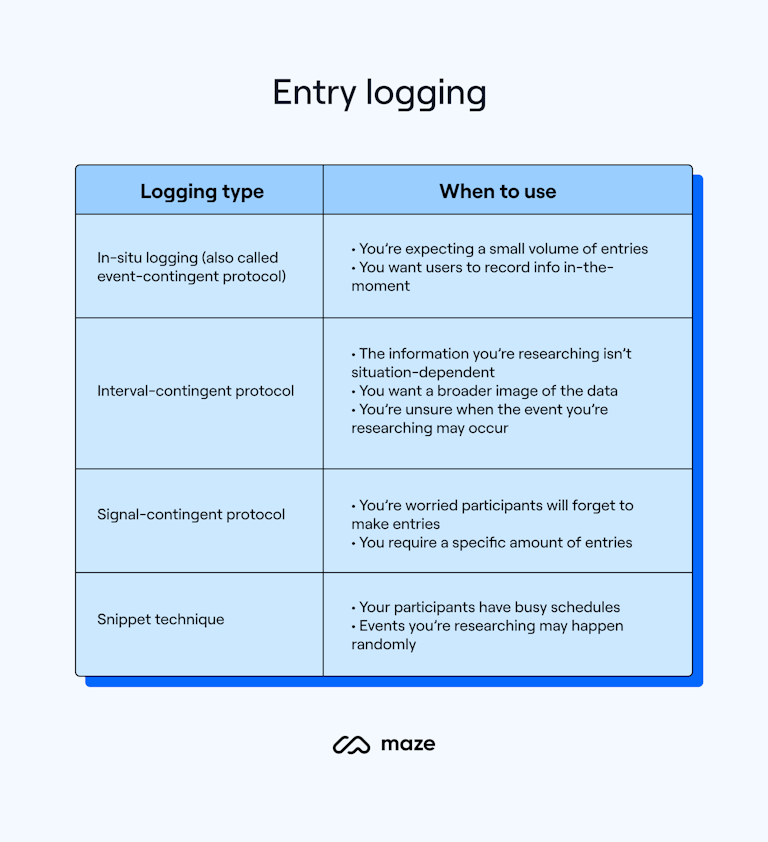

What kind of logging are you doing?

Before you can begin your study, it’s crucial to think about how you’ll ensure diary entries are logged. There are several approaches to logging:

- In-situ logging (also called event-contingent protocol): Participants log when a relevant event occurs

When to use: Since this method asks participants to log information as it happens, it’s best for research where you don’t expect high volumes of entries, as this could disrupt the participant’s usual activities, and would be difficult to analyze later. For example, if you’re researching fashion retail websites, one of the events you’d ask participants to log may be each time they think about or browse clothing websites.

- Interval-contingent protocol: Participants are given predetermined intervals to report into, e.g. asking for entries to be logged every three hours

When to use: This technique is effective if the research you’re conducting isn’t situation-dependent, if you want a broader picture of daily life, or if you’re unsure when the event may occur. E.g. If you're researching the use of infant toys, interval-contingent protocol may be useful, as it’s hard to predict the play patterns of young children.

- Signal-contingent protocol: Participants receive notification to log. These may be manually sent or set up to automatically notify participants at regular or pre-planned intervals.

When to use: This method ensures you’ll receive an adequate amount of entries (typically one per day, or more if you’re doing in-situ logging), and reduces the possibility of participants forgetting to log entries, however it requires a notification tool and participants with some flexibility (unless you tailor notifications to their schedule).

- Snippet technique: Participants report events in-the-moment in a quick way (e.g. a couple of words on a post-it or phone note), then use time set-aside later to expand on the snippet. This technique is less intrusive than others, while still ensuring immediate responses are captured.

When to use: Snippets are particularly effective if your participants have busy schedules, or the events you’re researching are likely to occur randomly or in different locations.

Preparing participants for a diary study

Selecting participants for any UX research is a daunting task, but this step is particularly tentative for diary research—not only do you need participants who can answer your questions, but you need users who are understanding of (and willing to adhere to) the demands of a longer-term study.

Why your research participants matter

Just as the materials you build with matter, the participants you research with matter. These are the people who represent your target user group, they’re the people who will be using your product first-hand, so their opinion matters.

Participants will inform so much of your product; from the shape of an icon or the color of a button, to the most core functionality, research participants’ feedback will influence any and all decisions. That means, it’s imperative that they fit the bill.

When recruiting participants, don't hesitate to mention the reasons for this choice of method; this is also an opportunity to explain what they gain from being involved with this method.

Matthieu Dixte, Product Researcher @ Maze

How to select diary study participants

Selecting participants for a diary study doesn’t have to be complicated. Here’s our formula for the perfect participants.

Participant profile + screening criteria x recruitment tool = great candidates

First, you want to build your participant profile (what your dream participant looks like) and consider any screening criteria (boxes they must tick). This will be heavily influenced by your target audience and research objectives—for instance, if you’re researching products for newborns, you want to ensure participants are new parents. Categories to consider include:

- Basic demographics (age, gender, marital status, nationality)

- Lifestyle (employment, hobbies, finances)

- Habits (schedule, interaction with products, type of customer)

Once you’ve narrowed down your ideal participant, use a recruitment tool with a built in screening survey for the most efficiency when gathering participants, and filter down to the best candidates. Bear in mind that few testers of more accurate profiles are better.

In terms of numbers, your study may require as few as three, or as many as 30 participants—this number will shift depending on the scope and budget of your research. For a typical diary study, we suggest aiming to recruit 10-15 participants, with a couple of back-ups.

One tactic for recruiting participants is to incentivize them, to ensure follow-through with the entire study. You can also consider working with existing customers; this is particularly valuable if you're researching changes or new features for an existing product.

Take a look at our article on recruiting research participants for more advice.

How to conduct a diary study

While diary studies can be left somewhat unattended, if you want them to be a success and gather useful data, you need to prepare them well, to ensure everything ticks over without a hitch. In this section, we’ll get into five steps for planning and conducting your diary research.

I always follow ‘KISS’: keep it simple and smart. Your study needs to be quick and easy for users to complete, with clear and detailed instructions, to ensure they complete it regularly and accurately.

Matthieu Dixte, Product Researcher @ Maze

1. Plan your study

First up, it’s time to get organized and sketch out the parameters for your research.

Determine your objectives

Start by reviewing your main objectives—are you researching an existing product, or a new one? Do you want to understand specific interactions, or broad behavioral information?

You can research multiple topics at once, but it will lead to more data to analyze, so ensure you link back any study objectives to broader research goals, to avoid being inundated with unnecessary information.

Select your diary type

By this stage, you should already have considered what type of diary (online/offline etc.) you’re using. But before you can prep your research or participants, you also need to determine the style of diary and entries. Choose from a freeform or structured diary, or even a combination, depending on your objectives.

Write your research questions

Now it’s time to collate the questions you’re hoping to answer, and put together any specific questions you’re asking participants—either as part of a structured diary, in general briefing documents, or follow-up surveys.

Some potential questions to consider are:

- Describe your day

- What were you doing before [event]?

- What was the hardest thing about achieving [task]?

- How did you feel before using [product]?

- What could have made [task] easier?

- How did you find using [product] today compared to last week?

Get 350+ examples of research questions in our research question bank 💡

Set your start and end dates

Some studies may only need a few days, while others can continue for weeks, or even months. The study length depends on your research goals, product and topic—will the data you gather in a short period of time likely be the same as that collected over several weeks or months? If not, it may be worth continuing the study for longer to ensure you capture any temporal dynamics and a consistent, median data set.

Work with participants to plan the best time for the study to take place—for example, if you need their full attention, is there a period with more free time? Or if you want to see how they interact with your product in everyday life, what period is their routine most stable?

2. Prepare participants

Next, it’s time to introduce your participants and prepare them for the study. Bear in mind that for maximum efficiency and quality of results, you won’t want to communicate with participants once the study is underway (unless you’re providing manual notifications).

Education is key: take the time to explain the format to your respondents. Try to be transparent about the pace and format of answers; this will improve engagement and response rates over time from users.

Matthieu Dixte, Product Researcher @ Maze

Now’s the time to make sure participants are fully briefed and understand the assignment.

- Create a ‘cheat sheet’ to guide participants (include key info about the study and how-tos, emergency contacts etc.)

- Provide any props needed

- Plan any rewards or incentives

- Walkthrough entry logging method

- Share any pre-study surveys

3. Progress with the research

Now onto the bit you’ve been waiting for—it’s time to start researching!

Unlike with other research methods, this is the time where you’re the most hands off. This means now’s the perfect time to plan your follow-up and data analysis, or work on other research simultaneously.

While your study is running, you may want to communicate more or less with participants, depending on your diary and logging type. Keep any reminders or notifications consistent, and remember to be human. Recognize the input of engaged participants, and check in on those who appear to be struggling. Participants are opening up a vulnerable part of themselves with the study, so respect their boundaries and provide guidance where needed.

If you’ve arranged for entries to be sent to you as they’re logged then you may find yourself overwhelmed by the amount of data coming in. Organization is everything, so take notes and process as you go—it will save a lot of time in the long run. For video or audio logs, either use a diary study tool that transcribes, or send entries for transcription.

Note: If you're already using Maze for your UX research, here's how it can help with diary studies, too.

4. Post-study follow-up

After your study comes to an end, it’s worth meeting with each participant as a chance to discuss entries in detail. If this isn’t possible, an asynchronous interview or survey works well, too.

Once you’ve read all the entries, you can use this time to conduct a post-study interview and ask participants to expand on information where needed, and ask any follow-up questions you remembered part way through or off the back of entries.

Tip: After the study is also the time to ask for feedback from participants—what went well, what could be improved next time, what did they learn? Use this information to improve future research.

5. Process the data and analyze

If you’ve been using a diary research tool, your data may already be sorted. However, if you’re using other methods of diary submission, the work starts now. Once your diaries are transcribed, it’s time to sift through the data and begin to identify patterns, synthesize hypotheses, and track trends.

To make the task a little easier, we recommend breaking it into two stages:

- Identify your top participants: Who stands out, with either a particularly robust set of data, or significant patterns? It’s much easier to find evidence for an existing pattern, so use these individuals for leading takeaways and other entries to support your theory.

- Tag your data correctly: While tagging data isn’t always necessary, it proves valuable for diary research. Go through responses and assign descriptive tags (e.g. activity types, like ‘housework’, ‘fitness’, ‘relaxation’). Next, work with teammates to create thematic tags (e.g. ‘fun’, ‘interesting’, ‘boring’). Finally, consider which tags commonly overlap to start identifying patterns.

With the right analysis, your raw data can turn into valuable insights which are ready to inform your design.

Alternatives to diary research

Of course, diary studies won’t always be the perfect fit for your research project. It has its downfalls—self-reported data may be unreliable, and keeping a diary requires significant dedication from participants. So, if you’re looking for immediate results, have a very limited budget, or are focused on a simple usability question, then diary research probably isn’t for you.

Some alternatives to diary research include:

- Surveys and questionnaires

- Interviews

- User analytics

- Focus groups

Diary studies can also be combined with other methods as a way to gather more data or expand the reach of your research while keeping to a budget. What’s more, opting for a second, quantitative data research method can provide more well-rounded results in combination with diary research.

Frequently asked questions about diary research

How do you write a diary study?

How do you write a diary study?

To write a diary study, you first need to determine the type of diary you plan to use. For an open/freeform diary, participants have freedom to write what they want when they want. For a closed/structured diary, you may want to write a set of clear instructions, provide questions for each day of the study, and write follow-up questions.

How long should a diary study last?

How long should a diary study last?

The length of a diary study depends on your objectives and research area. Diary studies can last anything from a few days to a few months.

When should you do a diary study?

When should you do a diary study?

You should consider running a diary study if you want to:

- Gather data with real-world context

- Understand micro-moments that build a big picture

- Capture temporal dynamics and how behaviors change over time

- Give participants time to think deeply about answers

- Minimize the impact of observation